SUBSTANTIVE NOTHINGNESS WITH BRENDAN PLUMMER

For Brendan Plummer, the ideal suburban life – complete with a stable desk job, nuclear family, and wife and dinner to come home to – is less of an American Dream and more of a nightmare.

The Sydney-based designer and recent UTS Honours grad describes his most recent collection Dust as inspired by “suburban grossness, people in accounting jobs and in shit buildings” that people come to expect in life.

“And it just seems so bleak.”

Over coffee, Brendan tells me about white picket fence ideals, the suburban town planning book The Geography of Nowhere, and about visiting development suburbs in outer Sydney where identical houses line the street, empty and waiting to be bought. Next to the already complete houses are ten more, half-built and covered in tarp.

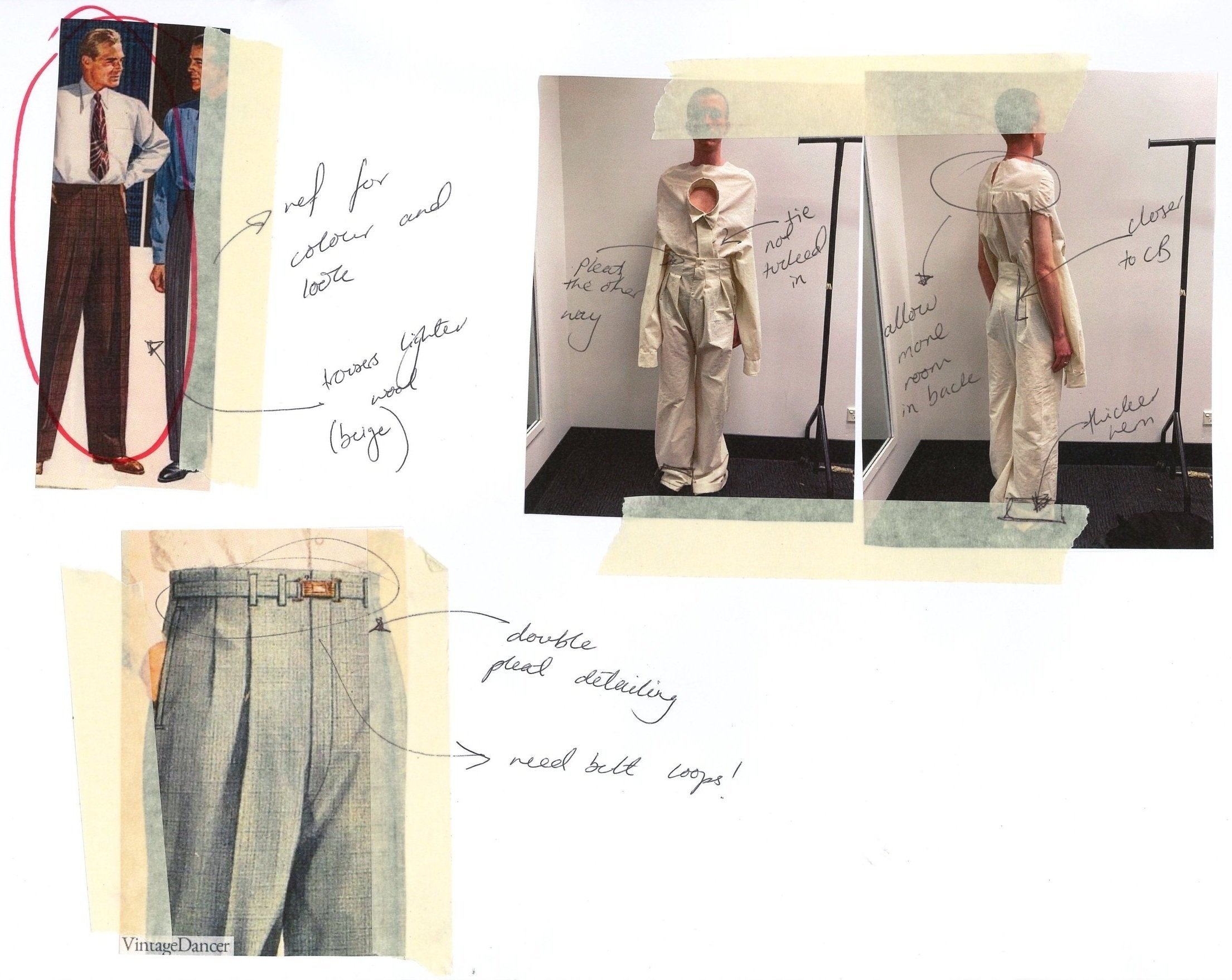

“That’s where the inspiration for the tarp came from,” he says, pulling up his first look on his phone. The model is dressed in something that resembles a grey-blue button-up, puffer vest and beige chinos – only, nothing sits right. His sleeves hang empty whilst his trousers merge into the tarp behind, likening him to one of the half-complete, mass-constructed houses.

The second look continues down the same subverted corporate-wear path — a white dress shirt made from a suit bag, zero waist pants and an excess of belts. It surprises me when Brendan says the belts (my favourite part of the look) were a last-minute addition, the result of eleventh-hour panic and an “oh fuck” moment about it feeling too blank.

But blankness, nothingness, and all their many synonyms are what lies at the heart of Brendan’s collection. His models are fitted with grey, identity-stripping masks, their specific shade taken from what you get after using the drag and delete function on Preview. When paired with his 50s inspired womenswear, it looks straight from a horror movie.

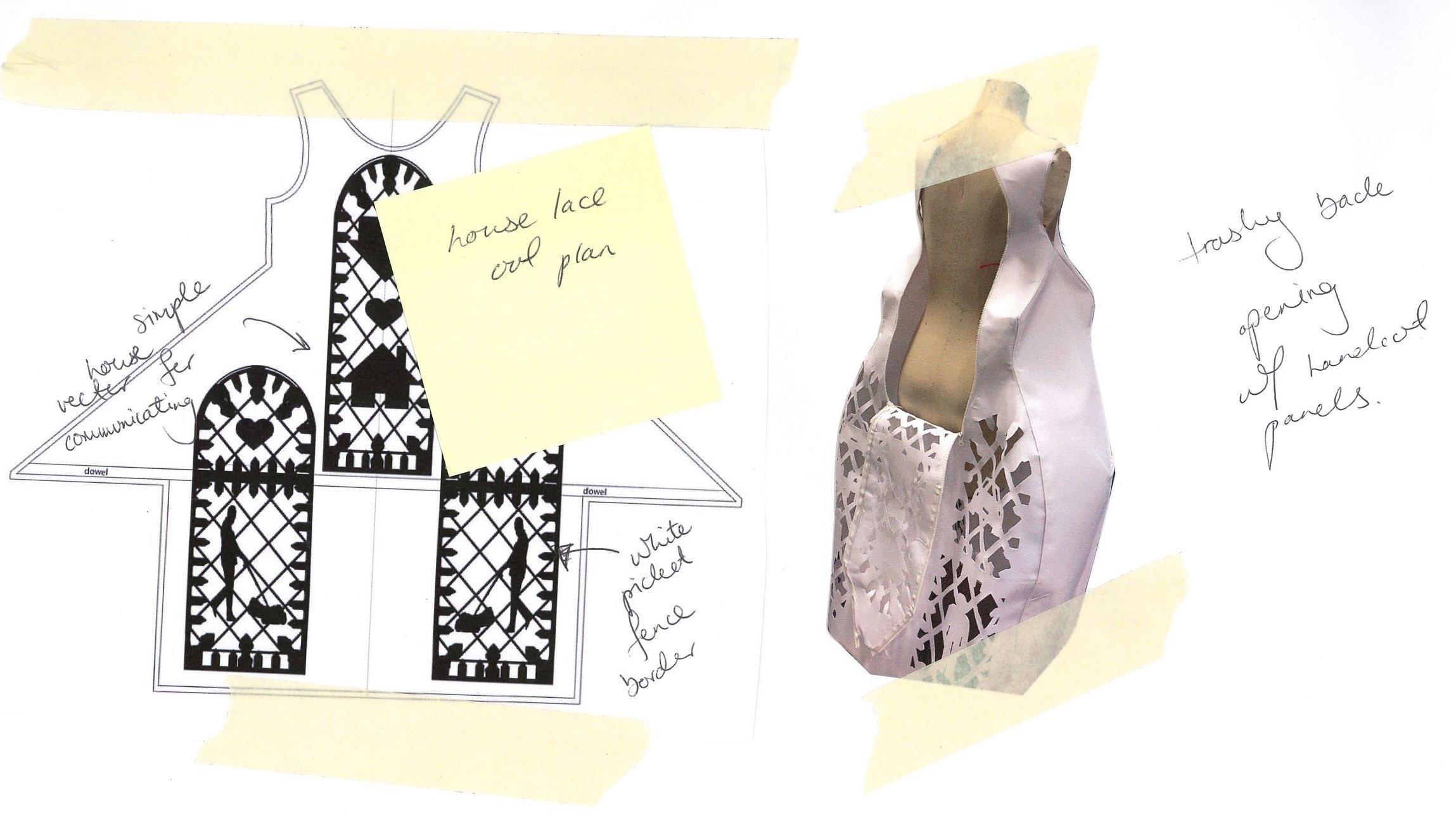

The collection reaches its crescendo with Brendan’s “wedding dress”. It’s the big finale, not only of his runway, but also as a symbolic resignation of oneself to the monotony of corporate-domestic life.

He tells me that the dress originally began shaped as a house and went through an excessive ten iterations before finally becoming something he was satisfied with. It’s meticulously detailed, with hand-done cut-outs in the structured satin fabric that show a man and woman, a car, and two upside-down houses with a heart in the middle.

Instead of a mask, the model is draped with a voluminous plastic veil that covers him like a piece of furniture. It’s a deliberately chosen material that Brendan tells me is a play on plastic’s dual function – both protective of dust on the outside, yet something that preserves it on the inside.

As he’s explaining this to me, I’m impressed by his thoughtfulness and the way his collection draws so deeply from both researched references and personal existentialism. More than just being “inspired by” something, he critiques, satirises, mimics and mocks.

When we’re nearing the end of our conversation, I ask Brendan what he’s most proud of. He tells me that it’s the fact that the final product (whose initial brainstorming process he had earlier called a “murder map”) actually came out simple and comprehensible.

“Most of the criticism in my process is that I just do too much thinking.” He says. “I just keep fucking thinking. One idea is so hard. You have all these ideas, but how do you say what you want?”

It’s an idea that anyone in any creative field can painfully resonate with. To have a creative vision or message is one thing, but its execution is an entirely separate feat. And although Brendan says he struggled, it’s clear he’s done a pretty fucking good job. The fact that on the night of the show, I spot multiple people wearing his designs is telling in itself.

With its bleak hues, structured materials and blurring of old-school domestic life with present day, Brendan’s collection hits at modern existentialism, capturing the site at which monotony morphs into stagnation.

Dust, because that’s what accumulates when nothing moves.

See Brendan’s full set of looks below

See more from Brendan Plummer here / Words by Sharyn Budiarto