ALEESE MUSA

ALEESE MUSA is a Sudanese-Egyptian videographer, dancer, and creative based in Sydney.

After working for Playground Vintage, Genesis Owusu, ConverseX, and Culture Machine Studios, it seems fitting that Aleese is penned by brands like Converse and Ellesse as one of Sydney’s most promising young creatives.

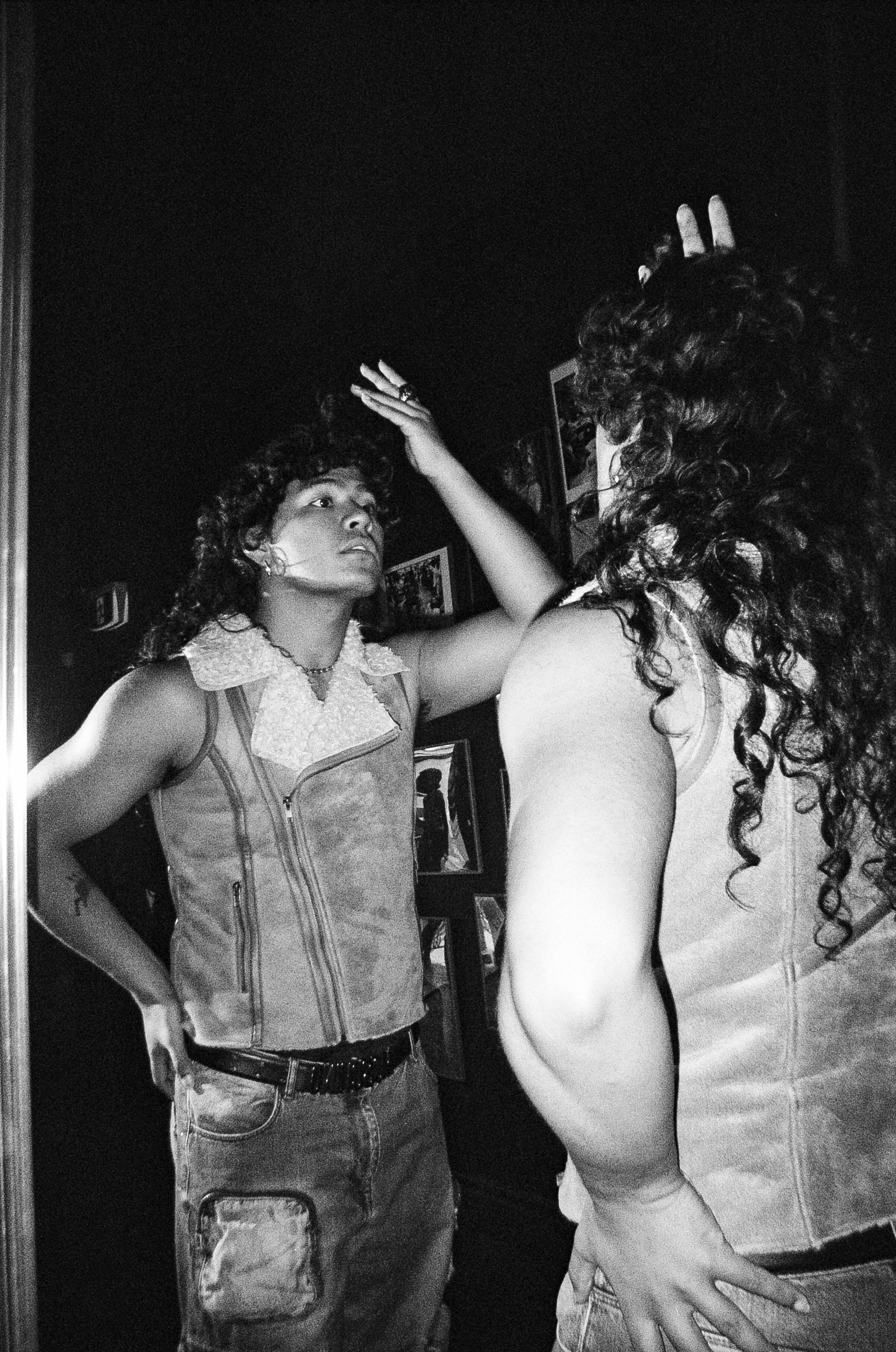

Aleese’s films proudly explore racial identity and Black culture through rich, vibrant colours and nostalgic, 90s-inspired fashion. Similarly, her personal style – marked by baggy fits and bold colours, patterns and layers – pays homage to her artistic influences and cultural heritage. Over sips of sickly-sweet bubble tea after our photoshoot, Aleese and I discussed the intersection of her cultural identity, style, and art, and the empowerment found amidst all three.

Even from a hundred metres away, I quickly recognised Aleese amongst the crowds surrounding the ICC theatre. She was wearing one of the three “distinctively Aleese” outfits that I asked her to curate for our shoot: a baggy sweater vest draped over a tee, layers of necklaces and serpentine earrings, loose denim jeans, and chunky sneakers.

Her backpack swelled with more of her signature pieces: a draping flannelette button-up. A glossy, chocolate-brown baguette bag. A vintage Chicago Bulls tee. Slinky sunglasses. Another pair of denim jeans. Each outfit was a nostalgic nod to the playful confidence and long silhouettes that characterised 90’s fashion, particularly within African-American cultures.

Aleese’s teenage clothing choices, however, starkly contrast against her current wardrobe of baggy, 90’s-inspired garments dripping with colours, textures, and layers. She once favoured monochromatic colours and subminimal styles, calling her previous self “a skinny jeans and plain tee type of person”.

“I was the only Black girl [at school]. I was super tall. I had a more masculine frame than the other girls in my year. I didn’t want to draw attention to myself as I stood out in high school so much,” Aleese explains. “I didn’t want to be associated with anything to do with Black or African culture, either. I posed myself as an Arab-Egyptian woman because I thought it’d be more impressive to be aligned with that, instead of being aligned with African cultures and identities.”

This repressive instinct is too familiar to many BIPOC living in Australia, particularly immigrant children struggling to find representation in their spaces. It’s a brutal and arduous journey that Aleese and I openly trade stories about. Having moved to Sydney from Egypt in 2000, Aleese was immediately thrust into Australian life: one of her earliest memories in Australia involves sitting on her mother’s lap amidst an Olympic crowd, donning t-shirts printed with the Australian flag, and cheering for their new country to win. And, whilst Aleese fondly reminisces on her childhood “full of good memories”, she admits that she wasn’t always immune to the cultural isolation and “othering” that triggered a sense of shame about her own background.

Aleese, however, acknowledges a rightful shift in her self-perception, and this is reflected in the sparkling glint of her statement earrings and chunky gold jewellery. She attributes this change to some timely cultural introductions: “Once I started listening to rap jazz and RnB, once I started watching Spike Lee movies, once I was more exposed to Black diasporic culture...I was like, holy crap, there’s such a diverse spectrum of style, attitudes, faces, people, colours…so I got more experimental.”

This gradual unearthing of her own cultural roots is what inspired Aleese to embrace self-expression; to take comfort and confidence in her own ethnicity and cultural background. This confidence translated to her newfound fashion choices: they paved the way for self-expression that Aleese long hid from the world.

1. Black and Indigenous People of Colour

“My wardrobe completely flipped… that’s when I started getting into thrift shopping, visiting consignment stores, and trying to find things to dress up and make my own. I got really into 90s fashion – baggy denim, oversized men’s shirts, lots of colours, clashing patterns – through shopping at Vinnies and Salvos. I didn’t want to go back to a place where I don’t want to be seen, and where I don’t want to be heard…I wanted to draw more attention to myself because I was more confident in who I was as a Black woman. As a tall girl, and as a Black woman, I felt like I can easily be perceived as masculine – but instead of counteracting this with hyperfeminine clothing, I now lean into it. I like feeling comfortable in my clothes and drowning in my clothes, but not letting the clothes wear me,” Aleese muses.

The same cultural unearthing is what inspires Aleese to create a “time-capsule of memories” evoking nostalgia and self-discovery, particularly through her filmmaking.

“I think this idea of me wanting to preserve memories comes from my parents not having a lot of photos, videos, or recordings of themselves. Growing up, from the moment I knew how to use a computer, I’d take every chance to capture a moment that I can watch for years to come… so my upbringing and culture definitely permeate its way into what I make [as an artist],” Aleese explains.

Aleese cites Spike Lee as a major artistic influence, and the themes of “identity, nostalgia and memory” as drivers for her work. This is reflected in her filmmaking style: “My videos have very vibrant colours and huge 2000s vibes. I like recording on camcorders, and I like the grainy feel of old videos even though I’m using new-world formats. I’m not even a 90s kid, but there’s definitely an older vibe that I want to go for when making my videos.”

In 2019, Aleese directed, styled, and edited a video titled ‘The Durag Series’, which explores Black culture and identity through the symbolic durag. As well as heralding this culturally symbolic fashion staple in her video, Aleese styled the actors in signature outfits from her own wardrobe, showcasing the loose and colourful silhouettes that defined 90s African-American fashion.

“For that video and a video shoot for Converse, I dressed my models in stuff that I had been collecting and thrifting for the last six years. The styling works because I make videos that aesthetically resemble the 90s and 2000s… and I want to show my heritage and style in my work,” she explains.

In the space between starting this project and writing the final draft, Aleese had continued to create beautifully empowering art. The video she created for @iintwari’s photography project, ‘Men Do Not Cry’, was exhibited at Carriageworks. She choreographed a piece for Nexus, a dance production by the University of Sydney’s Movement and Dance Society, and now runs her own classes at IMI DANCE. Impressively, she also worked as a Movement Consultant for Genesis Owusu’s performance at the 2021 ARIA Awards. But, when asked about the future of her art, Aleese shifts the focus from fashion to her familial roots: “I want to understand myself and my family a lot more.”

“I want to tell stories about my history and my family, starting closely with my grandma. She’s my only living grandparent: the only one I got to meet. I definitely want to make a video getting to know her, having a conversation with her. In the future, I want to be able to tell her story, and understand who my dad is – and by proxy, who I am,” Aleese answers. “Of course if she doesn’t want to, that’s fine, but I would really love to.”

2. Early descriptions of the durag call it “a cloth band worn around the forehead to keep hair in place” (Singleton 2021). It carries a deep cultural history: enslaved Black women used head wraps to keep their hair out of the way during labour, and Black men later used it to protect and create silky waves in their hair. Thus, it has long played an important role in African haircare, and in the 1960s, the Black Power Movement used it as a fashion statement proudly representing Black identity and culture. It was also a staple of hip-hop style in the 90s and 2000s, and has even inspired modern high fashion (see: the halo-adorned durag worn by Solange at the 2018 Met Gala). This footnote nowhere near explains the rich, deep history of the durag, and I recommend reading Saleam Singleton’s piece on the durag (written for the online platform Byrdie) to learn more about it. Then watch Aleese’s video. Source: Singleton, S 2021

It is that last answer that solidifies to me Aleese’s approach to art: respectful, genuine, and soaking with integrity and pride towards her roots. Her aim to later capture her familial heritage reminds me that digging down to your roots is a constant process of searching, learning, and unlearning.

Words by Cheyenne Bardos